The Round Thing

‘The past for poets, the present for pigs’

Samuel Palmer

In this piece I wish to explore some aspects the work of Welsh painter Ceri Richards (1903-1971), in particular his engagement with the thrashing maelstrom of interconnection between nature, culture and psyche. More than most, and in the passionate visual interpenetration of styles drawn from, among others, his two great Welsh poetic peers, Dylan Thomas and Vernon Watkins, Richards was true to the fusion of natural forms and cultural inspiration, as met through a passionate and spiritually engaged psyche.

Richards lived a life of engagement beyond popular forms, a life of integrity, and though a member of the Surrealist movement and a contemporary of, among others, Henry Moore, he has snuck under the radar of popular awareness, being to some extent ‘uncontainable’, or perhaps, Traditional in his neo-platonic disposition. Influenced early in his development by Kandinsky and the sense of a harmony of colours, Richards set about discovering ways of ‘painting music’, moving through Breton’s Surrealism (he attended the Breton lecture ‘Limits not Frontiers of Surrealism’) into a deepening engagement with the forces of life itself. Moved by influences as distinct as David Gascoyne and Walt Whitman, it could be said that Ceri Richards melded surrealism as an action for liberating the mind, with his innate strong sense of spirit and freedom, expressed through notions of social justice, internationalism and political breadth. He adhered to the axiom, extracted by Gascoyne from Breton’s musings, that “Beauty will be convulsive”, and through his affinity for landscape (inner and outer), as well as implicit orders of form, Richards grew into a student of “the mystery, the ‘unreality’ of ordinary things”.

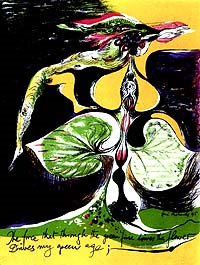

His peaks as an artist, to my eye, come in several bursts of mellifluous energy, in the sequence of paintings around Dylan Thomas’s ‘The force that through the green fuse drives the flower’, including 1944s ‘Cycle of Nature’; here there is an eruption of sexual-sensual organic life-form in a ‘biomorphic bacchanalia’ of joy and terror – an ecstatic art, with its lineage rooted into a Celtic foreground of ‘everything that lives is holy’; there are also later sequences returning to these themes, Cycle of Nature (1964-69) for example, or Summer (1968), and the elegiac hwyl-filled ‘Music of Colours: White Blossom (1968), inspired by the loss of his dear friend and soul-fellow, Vernon Watkins. Other notable series include the Beethoven paintings of the early 1950s. in which culture is the driving sensibility, the Artist-as-Genius; and the many paintings in the ‘La cathedrale engloutie’, inspired by works of Debussy and the way musical forms melt into landscape (the Gower coast, most often for Richards).

There are of course many other paintings of note besides, well worth exploring. Richards knew in his bones that ‘every force evolves a form’ – and perhaps his great nature cycles, early and late, best express this – with their vaginal, pod-like, astral-alien intensity, their organic traumatic cyclical agonies of renewal and death, their red heat in hearts blended to white drops in a natural orgasm of painterly, imaginal tantra. These forces are indestructible and in Richards’s hands they find their form newly made – almost akin to Francis Bacon’s (another contemporary of Richards) pronouncements on the ‘violence of paint’ in which remaking ‘the violence of reality itself’ is not a simple matter but one ultimately wedded to the ‘violence of the suggestions within the image itself’. However, unlike Bacon’s sophisticated cynicism of the deracinated eye, Richards holds the strange attractor of psyche up to the clashing spheres of nature and culture, shunning neither, devoted to both, and in his most sublime dedication created painting such as Afal du Brogwyr, also known as the Black Apple of Gower (1952).

There are of course many other paintings of note besides, well worth exploring. Richards knew in his bones that ‘every force evolves a form’ – and perhaps his great nature cycles, early and late, best express this – with their vaginal, pod-like, astral-alien intensity, their organic traumatic cyclical agonies of renewal and death, their red heat in hearts blended to white drops in a natural orgasm of painterly, imaginal tantra. These forces are indestructible and in Richards’s hands they find their form newly made – almost akin to Francis Bacon’s (another contemporary of Richards) pronouncements on the ‘violence of paint’ in which remaking ‘the violence of reality itself’ is not a simple matter but one ultimately wedded to the ‘violence of the suggestions within the image itself’. However, unlike Bacon’s sophisticated cynicism of the deracinated eye, Richards holds the strange attractor of psyche up to the clashing spheres of nature and culture, shunning neither, devoted to both, and in his most sublime dedication created painting such as Afal du Brogwyr, also known as the Black Apple of Gower (1952).This painting is of pivotal consequence and importance, for Richards and for us. A dark mandala encased in sky-sea-galactic contexts grappling for wholeness against the predicament of collective death. The painting gains even more significance when we realise that it struck Jung so deeply – he had been given a print of it by a Mrs Lucille Frost, a supporter of Richards – and a letter from Jung to Richards exists in which he expresses:

‘The round thing is one of many. It is astonishingly filled with compressed corruption, abomination and explosiveness. It is pure black substance…nigredo. Blackness understood as night, chaos, evil, the essence of corruption, and yet the prima material of gold, sun and eternal incorruptibility. I understand your picture as a confession of the secret of our time’

This powerful intrusion of utter darkness of nigredo into the Eden-like landscape of Gower is, metaphorically and literally, like a nuclear device exploding in the psyche – releasing all its potential, its infinitude of creative-destructive processes, held in the celtic knotwork of the core, a multivalent mandala pitchblende and poetry, holding the ambiguities and paradoxes within a vessel strong and gentle enough to cope. It is a sublime image of potential transformation. As Dylan Thomas wrote:

‘I dreamed my genesis in sweat of death, fallen

Twice in the feeding sea, grown

Stale of Adam’s brine until, vision

Of new man strength, I seek the sun’

Or as Vernon Watkins wrote in his ‘Taliesin in Gower’:

‘My country is here. I am foal and violet.

Hawthorn breaks from my hands.

I have been taught the script of stones

And I know the tongue of the wave’

After Watkins died Richards’s wrote ‘now that he is not there anymore the landscape seems deprived and inarticulate’, having lost its seer, its prophetic bridge-maker and image- shepherd. The loss is palpable, to one as tender as Richards, who had earlier faced the loss of Thomas too, asker of the ‘the deep and most persistent questions’, as had been Beethoven and Shakespeare before – images of the artist ‘searching for the right mutation’, reworking and remaking endlessly out of the prima material of experience, nature, culture and the cycles of time. Ceri Richards was the painter of cosmic sexuality, of organic unfolding, of curve and turn, of the feminine Sophia-light and her dark twin, of death and renewal made fleshy and ripe and, to paraphrase Nietzsche, he

‘himself becomes his images…. His ‘I’ is not that of the natural waking man but the ‘I’ dwelling, truly and eternally in the ground of being’

Richards died on 9th November 1971, exactly 18 years to the day after Dylan Thomas died.

KH

18.07.06

IMAGES: Cycle of Nature (1944), The force that through the green fuse drives the flower (1945), La Cathedrale Engloutie (Profondement Calme) (1962) all by Ceri Richards.

For more of the paintings mentioned above see the book Ceri Richards – A great Welsh artist by Mel Gooding (Cameron & Hollis, 2002).

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home