In Memoriam

For Dinah Williams born 13th July 1921 - died 13th April 2007

(Address for her funeral, given on 25th April 2007, by her grandson)

We’re here today to say goodbye to Dinah, my Nan, and to appreciate, indeed to celebrate her life here among us. We all knew her in our own ways, now they seem like precious ways; so let’s take a moment to see her life in context, her eighty-five years of gentle witnessing and mellowing love amid a tumult of change, both personal and collective within the wider world itself.

My Nan was born in 1921, when David Lloyd George was Prime Minister and King George V was on the throne. In her lifetime she’d see 16 prime ministers in all – almost 17, as Blair is apparently set to go inside a month or two. She knew 4 different British monarchs reign. When she was born, as part of the post-Great War baby boom, an old world of European empire was in utter ruin and a series of contrasting new shapes were struggling to emerge; new countries were being born out of strife – like the Irish Free State unfolding out of brutal civil war, or the country we now know as Turkey rising from the old Ottoman Empire, both were born alongside Nan in 1921. And who knew that even here in Newport 1921 saw a full scale naval mutiny, as sailors refused to participate in potentially being ordered to fire on striking miners? (Another sign of the post World War One realities Nan was born into – poverty, solidarity, hope for a better future, and of course the unresolved trauma of massive loss and raw grief). Some things about that year also echo in strange familiarity with today’s reality – in 1921 the British were busy occupying Iraq, for example.

My point is that Nan lived her life against the most intense period of technological and political change humanity has ever witnessed – in a sense this was her role, like many of her generation – to be a creator of domestic security, family love, a safe place in which to thrive as all around the world grew ever faster and more unfamiliar. In her 85 years, the same time it takes the planet Uranus to orbit our sun once, in that blink of a cosmic eye, she participated in a life anything but ordinary. Think of it – at her birth the fuel of choice for civilization was coal, by her teens it was oil and with that came the age of the motor car, of plastics, of urbanisation and mechanisation on a previously unthinkable scale. Despite trying several times, Nan never did pass her driving test so instead she witnessed the move from a world where a car was a very rare sight indeed, to there being one car for every 10 human beings on the planet, in one short lifetime. Speaking of which, Nan was born into a country of 44 million Britons, and a world population of about 2 billion people. Today there are up to 65 million Britons, and the Earth is home to about 6.5 billion people. Once again, a staggering change in the course of one lifetime, one generation. We could add in technological change too – from the Wright-Brothers to the moon landings and stealth bombers, from the discovery of antibiotics to genetic engineering and advanced heart surgery – something Nan experienced directly, but could never have imagined as a young woman. She also witnessed first hand the political shapes of Communism, Fascism, nazism, Socialism and today’s globalised corporate capitalism, together with their distortions, failures and legacies. Even the natural world changed too – from a relatively unexploited state of traditional and agrarian form, to a time where more people live in cities than any other setting. Of course, nature also gave up its forests, seas and aquifers in Nan’s lifetime, and took in the manifold pollution of human exploitation, so that we who stand here today do so in an age of uncertainty unlike any that went before, where even the ice caps are melting, the climate itself is twisting and jarring, and our sense of there being a future at all for life as we have known it, comes into a new doubt. We should remember too that since Nan was born hundreds, indeed thousands, of plant and animal species have gone extinct.

But why all this talk of context, all these outer forms? Well, because it is in the light of events like these, and especially in the vast changes they point at (and that I’ve merely touched on here), that Nan’s life takes on its fullest meaning. My Nan, who was to me the archetype of unconditional love and acceptance (and here I should point out that I think as one of her grandchildren, I got the very best of her – the fullest expression of her selfhood), my Nan was (and remains) a true teacher. She may not have even known it consciously, but she was. I remember her reading to me when I was very young, shaping my world and my imagination as she loved to do and I insisted she did – really, I couldn’t get enough. I remember her as tactile, warm, a rescuer, a soother, a source of constancy in a world of flux. And then I think of the moments I got to spend with her body the day she died, precious moments, her face still and relaxed after months of anguish. Peaceful. Still teaching me, as I held her hand and kissed her goodbye. To be honest I couldn’t help but smile at the incredible rightness of it all – this flesh and blood woman, so real, who I’ve known all my life, now gone, and yet even in her going she was still teaching me. Showing me how death is a friend we must all come to embrace. How there is no pain, no fear, no loss, no ending in that truth. Change is what we are made of, and in that swash of impermanence Nan was a pole star to navigate by and a hand held out to offer support.

I believe that my Nan spent a remarkable, ordinary lifetime living out her full being, giving herself fully to life. In her marriage to my Granddad she became part of the lifelong double-act that allowed her to express her true gifts. Her talent for nurturing, for creating safe and secure emotional spaces out of which come loyalty, acceptance, kindness, a capacity to put others first and to offer up a wonderfully soft yet unyielding compassion. She gave me my abiding taste for apple tart, a sense of wonder at her cleverness with practical crafts – she was a real maker, after all – and I’ll always remember how she seemed to know everyone and couldn’t go out without meeting someone (often many someones) to catch up with and chat to. Her world was rich with connections and community, unlike the multi-levelled alienation so many experience today.

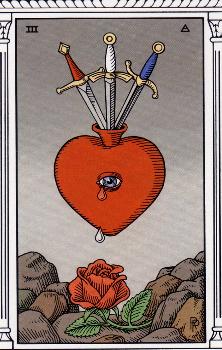

Amongst all of that, in her own way, though sometimes certainly afraid and confused, even appalled by the violence and distortions she saw in the world about her, Nan honoured herself and us, and in doing so gave us all a most precious gift – staying true in the face of personal and global shock and trauma, bearing with the constant change, and never losing that wide and infectious embrace of life and the many, many people around her, for above all else it was people she loved. Her heart was always true, and for me that is a reality ultimately far more real and important than any outer worldly event, because with a true heart the mystery of existing at all becomes approachable – with it comes humility, trust, openness, gentleness and warmth – the basic human goodness that Nan embodied so wonderfully. May we all create the causes for realising our own goodness, as she so surely did hers.

I’d like to finish by reading a poem that I think Nan would’ve liked. Its by the mediaeval Persian poet Rumi (translated by Coleman Barks) and its for all human hearts still intact and beating in this time of the Great Turning, when our fears are heightened and our integrity is most tested:

Quietness

Inside this new love, die

Your way begins on the other side.

Become the sky.

Take an axe to the prison wall.

Escape.

Walk out like someone suddenly born into colour.

Do it now.

You’re covered with thick clouds.

Slide out the side.

Die, and be quiet.

Quietness is the surest sign that you’ve died.

Your old life was a frantic running from silence.

The speechless full moon comes out now.

Thankyou Nan, for everything. Go well.

Image: Blue Hands, visual & performing arts department, Delaware State University

kh 22.4.07